A lot of unmeasured experience may be hiding from view.

We all, at one point or another, have known that sinking feeling of having missed the bigger picture. The worst times are when we’ve put a lot of effort, time, and analyst hours into a business decision that turned out to be missing a lot of important information.

Sometimes it can be revealed to us either by our manager, or a colleague, who will say out loud in the middle of a meeting:

“I don’t recognize these numbers you’ve got here.”

The bigger the data set, the more effort involved, these all add up to a bigger cost of hitting the skids. We all know the importance of what we tend to call sanity checks. But, how do you create a discipline for:

Catching missing data at the data measurement and gathering stages, versus the analysis stage?

Helping you think about what could be missing?

Three Easily Remembered Questions

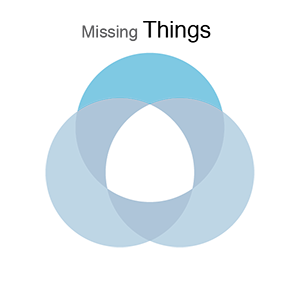

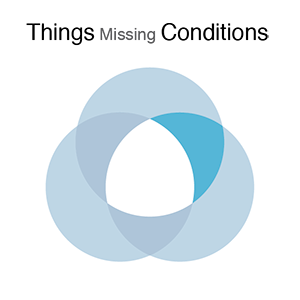

Having a complete set of data doesn’t mean just the entire file. It really means the entire measurable experience that matters. To illustrate that, our measurable experience can be simplified down to three basic questions: what are the things, times, and conditions?

Things. These are the subjects of our data story; the who, the what.

Time. Time is needed to measure change. We want to know about a whoor a what at two different points in time, so that we can make comparisons.

Condition. Condition is what we are comparing between two different points in time. For example, amounts, or locations.

An Example: A Troubled School Principal

Let’s put this into a real-world example. Imagine you are working for a school principal. She is concerned about student attendance, and wants the latest data to support a new attendance policy. You might go to the main office and ask for a report on absences. Later that day, you get back the following absence report:

A list of 100 students, showing that five were absent for more than two days between May 1 and May 31st.

Breaking this down:

Thing: Students

Time: Month of May

Condition: Absence of more than two days

Doesn’t sound too bad…and you might conclude that attendance might not be as bad as you think.

Until you showed it to the principal…

The principal looked at this report and said the problem is far worse. Why? As you listen to her response, we realize we might have caught these problems by asking the right questions up front.

What Did We Miss?

We missed out on a lot of experience that wasn’t measured. We are only seeing the above-water part of the iceberg.

We could have started by taking the report and asking some things-times-conditions questions (technically, we might refer to these as first order questions):

Students: Does the school in fact have 100 students?

Hang on, we have 110 students. 10 of them are from the district we annexed in January. That district uses 5-digit IDs, and we never reassigned them 6-digit IDs. So, the report missed them.

Days: May has 31 days. Why does the file only have 18 days?

Well, weekends aren’t included. Memorial Day wasn’t counted. But also, for 2 days, the attendance system was down.

Absences: Wait a minute. What do we mean by attendance?

Oops. The principal considers attendance to be either more than 2 days’ absences..or 1 tardiness mark. We are missing tardiness marks.

So far, we should have had:

110 students X 20 days X 2 conditions (absent, tardy)= 4,400 measurements.

But, as a result of what was missing, we only ended up with:

100 students X 18 days X 1 condition = 1,800 measurements

That’s only about 40% of the measurements we want. It turns out these small differences added up to a big difference in the amount of information we actually have.

Going Further

But, as it turns out, you don’t even have 1,800 measurements. When you look at the report more closely, and do some quick calculations, it turns out you only have 1,272 — only 29% of what you want. Why? We didn’t see even more measurable experience, stemming from the combination of second-order questions:

10 students are missing two days of time sheets.

It turned out their regular homeroom teacher was out sick, and the substitute forgot to turn in the timesheets.

8 students’ timesheets are missing tardiness marks.

They were on a work-study month-long assignment; their work sponsor only marked down absences. The students’ persistent tardiness came out in the negative written reviews.

There are 2 days in the report when we have null values for absences.

The system also had a two-day glitch, and didn’t record absences. The system only recorded tardy marks for those glitch days.

Between our first and second order information gaps, over two-thirds of our measurable experience is underwater. Why? Merely some ordinary glitches and poor definition of what we needed in the first place.

Seeing the Whole Picture, and the Problem

We’re using an iceberg analogy — and showing it using a Venn diagram. A Venn diagram like this can’t be perfectly calibrated to the proportion of information that is missing. However, it organizes how we think about the problem, and helps us visualize what’s there, and what’s missing.

Below is another example, in a slightly more interactive format. The topic: COVID-19 data. Many people at this very moment are scrambling to make sense of incidence data. Like many data projects, these support important decisions that can have real impact — and risk. You can see an example of how the data, when framed as things (counties), time (days), and conditions (cases, deaths), may have some missing experience. As a data scientist, or as a data visualization professional, you’ll need to identify these kinds of problems, communicate them to your audience, and decide how to manage them.

When you start your data project, you now have a way, at the beginning (!) rather than at the end, to:

Think about what you need

Ask questions about what might be missing

Visualize what you have, and what’s missing